Dear Reader,

Did you read that in Julie Andrews’ wizened Lady Whistledown voice from Bridgerton? No, you’re a straight man? Apologies, I’m still trying to pin down my audience. Double entendre intended.

This is my first post of what I’m guessing will be a highly inconsistent blog primarily consisting of film and book reviews, all extremely amateur and woefully un-researched to be sure (I heard you like irreverence), but all in some way pertaining to “ladies of the night,” the “demimonde,” or… “courtesans.”

If you’ll allow me to be clumsily earnest for a moment, I’m writing this blog in order to work on my writing skills, share some personal viewpoints that don’t fit in tweet format, and hopefully build some sort of bridge between myself and other temptresses, as well as with the men who adore us. Who knows? Maybe the odd lost-and-confused voyeur, too… I’m sorry to disappoint those who are hoping for a smutty read. That kind of thing doesn’t interest me, nor would I do it for free if I were.

The business side of me briefly considered saving time by prompting a language AI to draw up a “saucy, trollop-y reaction [to the book] that would be simultaneously interesting to SWers as well as …entertaining… to our admirers.” However, in some pretty impressive gymnastics of ego, and a stunning bankruptcy of judgment, I decided not to do that, so I will probably certainly fail in my attempt. And now that I think about it, it would probably end up taking more of my time and energy to beat the generic AI tone out of such a result, than it would take to simply write something on my own. So, rest assured, no AI here. This writing is all-natural, just like my… Well, anyway…

Let’s begin.

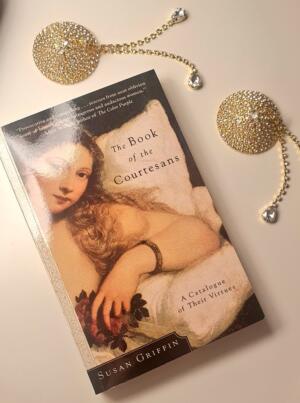

My first book review is on The Book of the Courtesans, by Susan Griffin (2001, Broadway Books). Surprisingly, other than a book of poetry I read last year by actual SWers (Hustling Verse; ed. Dawn and Ducharme, 2019, which was very powerful by the way and available at the public library), this is the first book I’ve ever read devoted to shedding light on the lives of actual historical women (and one man) whose lifestyles in one delightfully tawdry respect resemble my own. Although purporting to be a work of non-fiction, the book seems to be quite liberal with historical interpretation, and some aspects of the tales told are apparently outright invented, according to many book reviewers who seem far more scholarly than I. Still, overall, I’m glad I read it. In case anyone else is in a similar boat as me, and would like to dip their toes into this subject matter for the first time, I’ll go over my impressions here.

First, let’s take a quick look at our author, Susan Griffin, via her wikipedia page. Born in LA, she studied writing at California’s top schools and developed into a (quiet voices now, let’s not shout) radical feminist (aka RadFem) philosopher, essayist, and playwright. Although in Courtesans she never endorses the courtesan lifestyle in absolute terms (and I can’t find any info on whether she ever was or is a SWERF), she writes about it very enthusiastically and often admiringly. I will not go into any more detail about Griffin herself, as this book was published 24 years ago, and she is likely tired of hearing people’s critiques by now.

Griffin organizes the book along certain themes: seven “virtues” a good courtesan must possess. These include Timing, Beauty, Cheek, Brilliance, Gaiety, Grace, and Charm. I do understand the cuteness of the seven virtues cliche, but I would also add: (8) Care with Finances, (9) Self-Defense and Boundary-Maintenance, and, for our modern times, (10) OPSEC for Privacy, Cybersecurity, and Protection from the Law, as well as (11) Mental Health Maintenance.

It’s worth noting that most of the “courtesans” mentioned in this book were White Europeans living in times and places where SW was not only decriminalized, but in some cases, generally accepted by society. Not all of the biographical sketches in the book would fit the strict definition of courtesan, but I would say that stretching the official definition is actually a quite interesting exercise in defining SW. Was your engineering TA who offered extra tutoring for sexual favors a john? Was your friend who uses Tinder as a way to get nice meals a SWer? People are perennially divided on these questions, and it’s interesting to see them applied in a historical context. Probably half or more of the “courtesans” profiled in the book were actually mistresses, what we’d now call sugar babies, or women in showbiz just trying to get by.

Given the book’s division by “virtues,” rather than by eras, locations, or individual biographical sketches, I must admit I found the book rather difficult to traverse. Disconnected sidebars called “Erotic Stations” (seeming to act as fluffy artificial transitions between sections) further decreased continuity. The real problem I had is that, despite the book containing a glossary of terms and an 11-page bibliography, it completely lacks an index or any footnotes, which further gives a sense that the author could be making up any of it. Griffin habitually breaks up multiple narratives into sentences or paragraphs, interspersed and interspaced by multiple paragraphs or pages, but not logically so, and this structure made it all but impossible for me to actually follow any train of thought, and I soon gave up and read simply to catch some interesting bit of trivia here and there.

In essence, this is kind of a fluffy book full of some nice thoughts and sentiments, semi-disguised as an entertaining history book. I would be remiss not to note the overly-flowery language. I get that we are supposed to feel immersed in the sensual world of the working girl (and to be fair, sometimes I did feel that), but her tone definitely became cloying pretty quickly for me. I also felt that, since it’s dangerous for anyone to clearly say they are SW-friendly, the writing, although often complimentary to its characters, never seemed to choose either detached scholarship, or enthusiastic support, and that felt wishy-washy to me. But I do understand that even putting out this book in 2001 was a brave undertaking.

2001 was long before 4th wave feminism hit (the last roughly 10 years up to and including now when feminism became mainstream in the US), a time when all feminists were considered by most of society to be ugly, butch lesbians with mental issues (even by other women) and not to be taken seriously under any circumstances. I am sure Griffin was unjustly received this way by many.

This was published way before OnlyFans, founded in 2016, which for the first time gave female porn creators power over their content and individual narrative, instead of the male studio producers, website owners, and magazine editors and executives.

In 2001, a teenaged Britney Spears was mentally abused and paraded around sexually by her male-run record label (Jive Records) for the male gaze, at least partially against her wishes, and that was just normal at the time. The public never heard her story as a woman, and not just a commodified product, until 20 years later.

At the turn of the millennium, a woman’s pleasure was still quite taboo, especially compared to today. Most American men at that time didn’t know what or where a clitoris was. A frightening number of women didn’t either, until they watched Sex and the City. Women’s sensual, sexual stories were almost never told in popular culture at that time, so Sex and the City, written by Sarah Jessica Parker, was revolutionary in that regard (though not my cup of tea). However, Griffin would have done her research, and perhaps the writing for this book as well, prior to SATC coming out.

Despite The Book of the Courtesans’ subject matter being mostly long-deceased women, given the climate between the sexes in 2001, there had to have been something brave about a woman daring to attempt to tell the story of courtesan life from the perspectives of the women involved, albeit by proxy. The writing of this book had to have been somewhat transgressive in this regard, so I truly give the author her due flowers there.

I will also say that, as someone who had never read much about courtesans and their ilk before, this book was quite a decent introduction for me, and piqued my interest to read more. There were some illuminating moments I thoroughly enjoyed. I learned that some famous women of the night had been accomplished, published writers, including Mogador (French, 1824–1909), and Tullia d’Aragona (Italian, 150?–1556), to name a couple.

Whether it’s true or not (I haven’t the time to verify), one quote in the book by Mogador, who was a famous dancer as well as writer, really resonated with me, in regard to the recent success of the movie Anora, directed by Sean Baker. After Mogador read Émile Zola’s (a male Naturalist novelist) portrayal of her friend Pomaré in his novel Nana, Mogador was not only angry, but profoundly disappointed, it sounds to me. Her friend Pomaré was also a famous dancer known popularly as “la reine Pomaré (Queen Pomaré).” Although it seems Pomaré overcame a lot of adversity in life, and was far and away known for being an almost mythically successful dancer, Zola apparently reduced Pomaré’s character to simply having been a wretched hag selling raggedy second-hand clothes in her old age. Mogador’s reaction:

“Is this what Naturalism is? […] Is this their idea of precise detail?”

This succinct plea for some humanity, some empathy, embodies the reaction many SWers had toward the character Anora’s portrayal. By the end of Anora, all we know about the eponymous character is that she was dumb, foolhardy, and forever broken as a result of her poor choices. Scenes of her being assaulted are presented as comedy, and I have personally read many men online who found it hilarious. We learn nothing of who Anora is as a full human being, including her background, dreams, or any preferences on anything besides money, really. This is because Baker’s eye as a director gives away his personal POV that most audience members have totally missed: the SW client who has been completely closed off emotionally by his SWer, likely because she just doesn’t trust or like him at all. The truth for many SWers, including me, is that we often will share something about ourselves, even if only obliquely, with clients we like and trust. Imagine being Sean Baker, and proclaiming to the world through your artistic project, that you’re an unlikeable client. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn Zola had some issues as well.

In Mogador’s quote, I hear what so many of us SW sisters feel: despair that our stories are told so reductively and in such a male-biased way, by a man who wins fame for doing so. And seeing this happen again and again, tale as old as time, throughout our careers. I hear in Mogador’s quote a feral cry for justice, at the fact that Zola’s/Baker’s half-blind visions will color society’s perception of us for years to come, and we SWers will be stuck having to navigate the cultural climate he created. Again, I haven’t read Nana, or verified the quote, but it was just too real, felt too immediate, for me not to comment on it.

I, Annie, in 2025, empathise with Mogador from over a century ago. The character of Anora is Zola’s characterization of Pomaré. Baker is Zola. And this age-old cycle of men telling our stories for us, for profit, needs to end. Courtesans has its issues, but I appreciate it having come from a woman’s perspective nonetheless.

There are many other moments in Courtesans that feel enlightening or at least caused me to bookmark historical persons and events to look into later. If you feel like introducing yourself to new and colorful historical characters, and getting a rough idea of the history of SW from a European standpoint, definitely check out the book. However, if you’re a stickler for verifiable historical detail, perhaps look for something else.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, and are feeling saucy, book me, or go on and buy me a gift from my wishlist. Yes, I value my brain and enjoy using it. But I’m also a little materialistic. Those aren’t mutually exclusive, you know.

Yours, if you treat me right,

Annie